opera in 12 images by Sarah Nemtsov

with a libretto by Mirko Bonné

for 12 soloists, choir, orchestra and electronics

WP May 13th 2023 Saarländisches Staatstheater Saarbrücken

program note:

The opera OPHELIA is based on William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet (1602). The opera’s focus is, however, not on Hamlet, but instead (as the title suggests) on Ophelia.

Around 2019, the Saarland State Theatre (under the directorship of Bodo Busse) approached me with the proposal to compose a Shakespeare opera (as a continuation of the theatre’s Shakespeare cycle, which has grown over several seasons). Daniela Brendel, Promotion Manager for Stage Works and Dramaturge Ricordi Berlin, suggested that the role of Ophelia could be interesting for my opera. Indeed, it immediately “clicked,” because I had always been annoyed with the way her character is treated! In the course of Shakespeare’s drama, Ophelia is manipulated, used, abused, and alienated; she is ignored and (despite her intelligence) is not taken seriously. And at the end, when she begins to write poetry and to sing, she is declared insane – so that ultimately even her self-determination in death (be it an accident or a suicide) is taken away. She is romanticised, eroticised, made out to be an object of desire, a projection surface, a mirror, and a plaything. It is reminiscent of the fates of too many women over recent centuries and so I had the urgent wish that Ophelia would step out in this opera, would free herself. The result is an opera in 12 scenes (with electronic interludes) for 12 solo voices, choir, orchestra, and electronics.

I approached the author, poet, and translator Mirko Bonné for the libretto. I had already worked with him several times and set poems of his to music. I have an extraordinary appreciation for his use of language; it leaves a special space for sound. As a translator, Mirko Bonné has, among other things, translated Keats in his entirety (for which he rightly won an award. it is a great achievement). Mirko Bonné seemed ideal for this new transfer and transformation of Shakespeare’s drama. What should happen, however, I left open. I had only one wish, that there should be four Ophelias, and at least one of them should survive! The creative process was shaped by a mutual respect and by leaving space for one another, while at the same time we were also in exchange and certain wishes and modifications still arose during the work’s composition. Sometimes, for musical-dramaturgical reasons, text was deleted or changed, but the omitted text then flowed indirectly into the music; these text passages were in any case significant for the score! In a certain way, the four Ophelias are an echo of a previous idea (unrealised, but one that had occupied my mind for a long time) for a musical theatre piece about four 20th Century female writers: Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Janet Frame.

“Ophelia” sketch from a theatre performance by Elisabeth Naomi Reuter, 1962

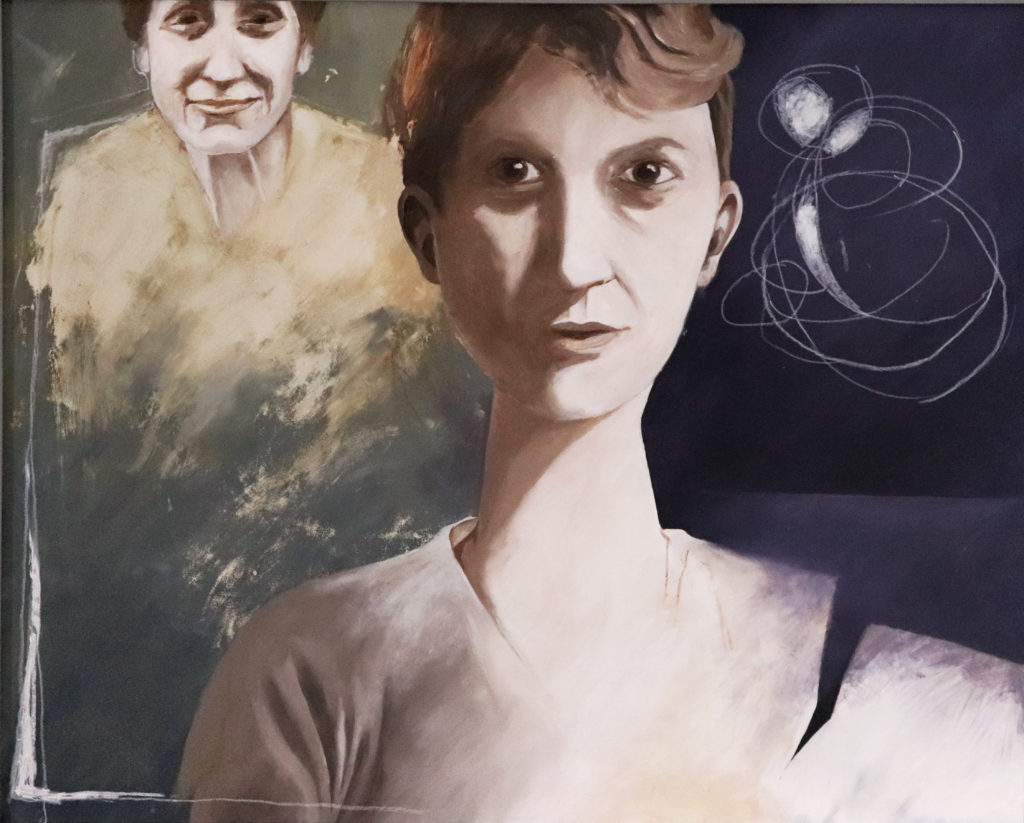

“The Moon is no door” (hommage à Sylvia Plath) by Elisabeth Naomi Reuter, oil and oil chalks on mdf board, 2015

“Virginia W.” by Elisabeth Naomi Reuter, oil on canvas, 2014

Mirko Bonné’s libretto (in verse and rhyme) picks up where Shakespeare’s drama ends. Everyone is already dead, and there are only three survivors: Ophelia (1), Horatio, and Fortinbras. The dead, however, find no rest – they are ghosts, on the threshold, occupying an in-between world, unreconciled with their lives, with their deaths, and with one another. They form an Ensemble of the Dead: Hamlet, Gertrude, Claudius, Polonius, Laertes, Rosenstern (the name a wonderful hybridisation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern), the three other Ophelias, as well as the Grey King, Hamlet’s father – the “chief spirit” so to speak. They are restless in their quarrels. Their dialogue occasionally tips over into the comic or tragicomic. They still argue about guilt, bring up the past, are consumed by revenge, shame, feelings of guilt, pain and longing, and would almost kill each other again. Their singing is likewise agitated and polyphonic, yet there remains soloists in the group, individuals, characters – (too) close to life. The group’s singing is then also different from the Great Shadow Choir. The Shadow Choir is made up of the dead, who are already much further away, by ancestors who have long-since passed, and are perhaps almost forgotten but are still there to be felt. A kind of indeterminate, almost unknown mass, a little eerie, but also comforting, their singing is mostly homophonic, dark, but not as dark as the rest of the music, it has some light, occasionally smouldering from the depths of time. The Shadow Choir is like a magnet or a black hole that attracts the other spirits (and sometimes the living) and eventually in the 10th scene also “swallows up” the Ensemble of the Dead.

The Ensemble of the Dead is a heterogeneous group; in a certain way it consists of nothing but outsiders. The Grey King is an actor without speech, sung by four male voices (as a reference to the four Ophelias), Prince Hamlet is also an actor (Hamlet: the prime role!), but he is lost in the opera; he cannot sing. Gertrude is a high coloratura soprano, and a particularly interesting role for me; the inwardly torn mother (and who know what kind of person her dead husband, king Hamlet, had been… who ever asked?). There are other high voices too: Laertes (as a so-called “trouser role” in tonal proximity to Ophelia, the sister who is loved too much) and Rosenstern (countertenor) not only on the threshold between life and death, but also on the threshold of the voice itself and that of the audience. Claudius drones and Polonius barks, and both try to cover up their insecurity and moral abyss. Horatio is one of the few characters with some integrity, which is perhaps what saves him from death. And young Fortinbras is a boy whose voice is breaking, on the threshold between child and man, a symbol for hope and future.

The story of Ophelia’s self-rescue or self-liberation is not, on the surface, told linearly, but develops rather subcutaneously. The possibility of liberation arises not least from the realisation, on the part of the other three Ophelias, of one’s own situation (or situations). They may be perceived as three different women, or as iridescent facets of singular self. With the end of the 10th scene, the Ensemble of the Dead finally dissolves, and the spirits become shadows, become fog, almost nothing, and by the 11th scene Ophelia is alone, freed from everything and everyone, and is finally with herself. She has walked through her traumas. The past has been let go, though it has not been forgotten, but Ophelia occupies the now, is open to what is to come. Here there is no sound other than herself, and her voice is finally allowed to show all of its colours – the darkest and the lightest, the delicate and the strong. Even the orchestra is no longer required. And no conductor. This act of liberation can certainly be read as feminist and emancipatory, but at the same time for me further meaning – beyond gender – in the empowerment of one’s own lost, buried, or suppressed voice, for the marginal, the deviant, for truthfulness and authenticity (in the awareness that 100% authenticity would be utopian), for the courage to be vulnerable and empathetic. Ultimately, it is here that the chance for a real encounter arises.

The image of the threshold could even apply to the entire opera. It doesn’t have to be interpreted this way, but one possibility to see it as a near-death experience. Everything takes place in Ophelia’s head alone – as in reports of near-death experiences, when the mind detaches itself from the body and in this suspended state the past flashes by in a kind of time-lapse. At the end Ophelia heaves herself out of this in-between world, pulls herself out of the water.

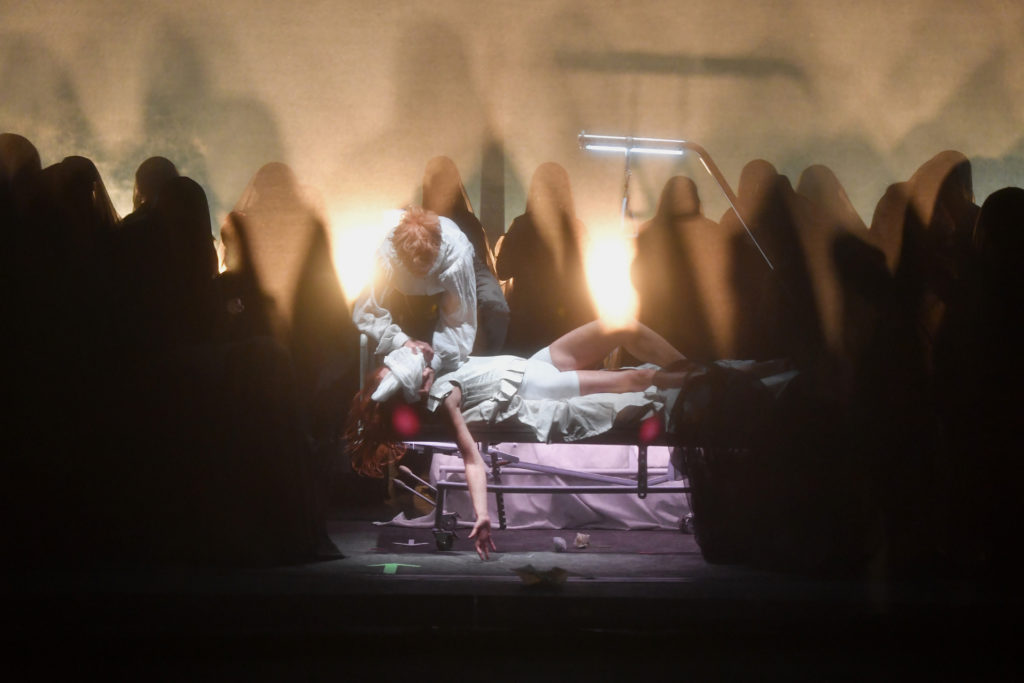

Valda Wilson (Erste Ophelia); Opernchor | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

links: Max Dollinger (Horatio); in der Mitte: Pauliina Linnosaari (Dritte Ophelia), Valda Wilson (Erste Ophelia), Judith Braun (Vierte Ophelia) und Bettina Maria Bauer (Zweite Ophelia) | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Ensemble | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Valda Wilson (Erste Ophelia); Christian Clauß (Prinz Hamlet) | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Ensemble | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Ensemble | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Valda Wilson (Erste Ophelia) | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

Valda Wilson (Erste Ophelia); Max Dollinger (Horatio) | Foto: Martin Kaufhold

I also tried to depict this aspect musically by clearly defining the Ensemble of the Dead as a group of different characters, and at the same time sending compositionally specific material through all of the voices, like a red thread, so that the chants could emerge from one head like a thread of thought. In the music different times are embraced, the harpsichord (for instance) as a trace of the era of the baroque opera, but also a synthesizer and electronic drums as a sign for 21st century’s club music.

The Shadow Choir was also recorded using 3D technology for the electronic interludes; these appear between the 12 scenes and frame them – connecting and delineating them at the same time. Collages in space of (ghost) voices (that are unexpectedly near), noises, electronic sounds, and more, all programmed in 3D to create an immersive sound experience for the audience.

The orchestra in the pit expands everything with another dimension. On the one hand, the colours of the “plot” are traced, on the other hand, the orchestra is sometimes soloist or ensemble, it can support the voices and give them space, give them depth, comment on them, but also contradict them and sometimes kind of swallow them up or wash over them.

Harmonically, the opera moves through certain panels and shades, sometimes contrasting, sometimes complementary. There are quite different textures and different speeds. Surfaces, abysses, and expanses can therefore emerge, but so can densely packed structures, flickering or dark pulses, all the way to frenzied dances. Ultimately, life is to be embraced.

The opera is dedicated to my daughter Leah.

And to the memory of my mother Elisabeth Naomi Reuter z’’l.

***

Special thanks go to: the Saarländisches Staatstheater, Bodo Busse, Mirko Bonné, Daniela Brendel, Martha Agostini, the entire Ricordi team, Robert Schenke, Matthias Erb, Stefan Neubert, Eva-Maria Höckmayr, Fabian Liszt, Valda Wilson, Tutti Reuter, Christian Wollin, Mathias Kroll, Aribert Reimann, the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation for their support – and last but not least: Leah, David, Elias, and Jascha for their patience and love.

Sarah Nemtsov, Spring 2023

commisioned by Saarländisches Staatstheaters with the support of the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung

publisher G. Ricordi & Co. Bühnen- und Musikverlag GmbH – Berlin

***

TEAM:

Conductor Stefan Neubert

Stage Director Eva-Maria Höckmayr

Stage Design Fabian Liszt

Costumes Julia Rösler

Sound design Matthias Erb

Dramaturgy Anna Maria Jurisch

Choir Jaume Miranda

Soloists:

Ophelia I (Soprano) Valda Wilson

Horatio (Baritone) Max Dollinger

Claudius (Bass) Hiroshi Matsui

Gertrude (high Soprano) Liudmila Lokaichuk

Prinz Hamlet (Actor) Christian Clauß

Polonius (Bass-Baritone Buffo) Markus Jaursch

Ophelia II (lyr. Soprano) Bettina Maria Bauer

Ophelia III (dram. Soprano) Pauliina Linnosaari

Ophelia IV (lyr. Mezzo) Judith Braun

Laertes (Alt) Melissa Zgouridi

Rosenstern (Counter) Georg A. Bochow

Der graue König (actor) Alois Neu

Fortingbras (Teenager boy) Kostyantin Matslov / Benjamin Schmidt

Saarländisches Staatsorchester

Opernchor des Saarländischen Staatstheaters

***

WP 13.5.2023 Saarländisches Staatstheater Saarbrücken

further performances 19.5., 27.5, 4.6., 11.6., 24.6. und 28.6.2023

***

Links

Interview Saarbrücker Zeitung

Poly Magazin (Französisch)